Four days after I learned there are zero tumors inside my skull, the country I live in elected Donald Trump. I had almost no time to grapple with the long-reaching consequences of my MRI results when I faced the long-reaching consequences of emboldened white supremacy masquerading, as always, as economic trepidation.

The absence of tumors on my eighth cranial nerves means exactly that: there are no tumors on my eighth cranial nerves. No ah-ha! moment to explain my neurological symptoms or give me the damaged gift of diagnosis. No certainty to set me on a path towards treatment and prognosis. By treatment I mean brain surgery, and by prognosis I mean deafness and maybe blindness and definitely more tumors and surgeries and crippling pain for the rest of my life.

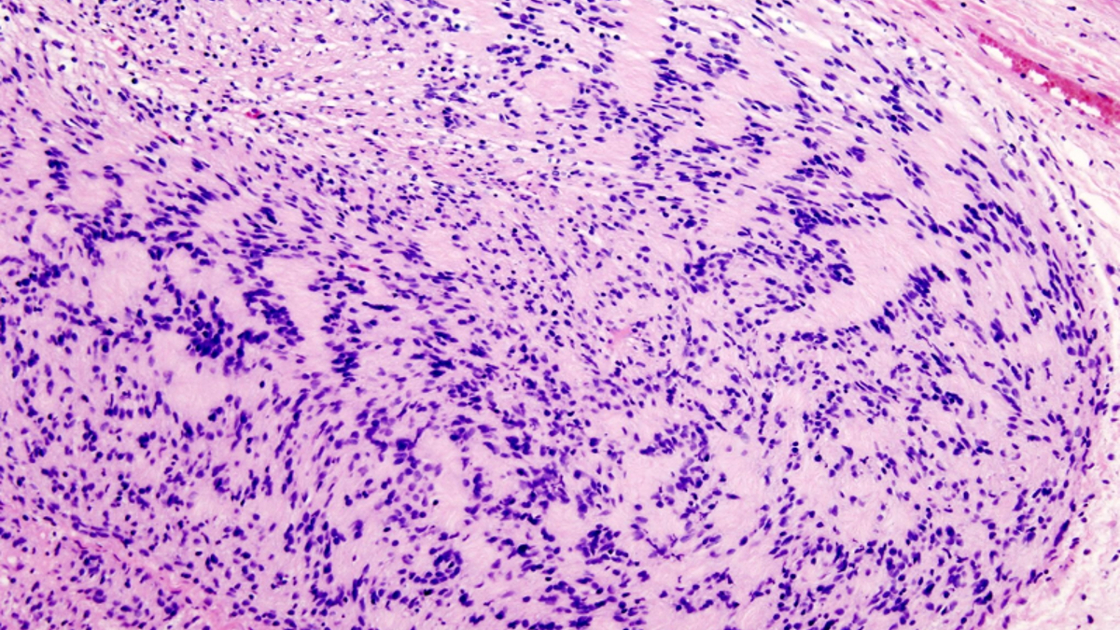

Instead, I am left with starting again, perhaps not all the way back at square one since I have a confirmed schwannoma and family history of some kind of neurological tumor condition. That family history now includes my older sister, whose painful right shoulder is now confirmed as another manifestation of this terrible thing that has affected our family for generations. But because science has advanced so much in the thirty years since our father’s clinical (rather than genetic) diagnosis of Neurofibromatosis type 2, it seems pretty clear that my family is actually affected by schwannomatosis, a type of NF that wasn’t even identified in the dark ages of 1987.

For years we – my sister and I – have circled around NF2 literature, learning as much as we could tolerate during rabbit-hole dives in the years between Al Gore inventing the internet and each of us getting our tumors confirmed. And now that we’re here, with tumors and nerve pain keeping us up and waking us up so that we haven’t had a single night’s sleep that hasn’t been interrupted by you have the thing that killed your father agony in nobody knows exactly how long, starting again on the path of diagnosis often seems enormously daunting. But mostly, it is just another round of the shoulder-to-the-wheel work we already know how to do.

It is the work of genetic testing, of waiting between appointments, of navigating the maze of a health care system that supposes itself providing patient care when in reality it is just another factory focused on patient processing. But I come from a family afflicted by a genetic condition, and part of that includes knowing how to be as easily a processed patient as possible, so that my treatment and care might be as efficient and effective as possible. This much I can control, amid a bleak ocean of things no one really can.

There are so many unknowns right now. Will my neurosurgeon be able to remove my entire sciatic tumor? Will there be extensive nerve damage? When will I develop another painful schwannoma, and where will it be? And inside each of these questions hides the most terrifying of them all: how will the political climate of the Trump-era United States affect my ability to receive the treatments I need to keep me mobile and alive?

My father became a quadriplegic in the pre-ADA days of the Reagan era. I remember the crushing tragedy of his sickness, a tragedy born more of the anti-disability climate of the time rather than his actual physical condition. Had my father lived in a society that mandated wheelchair accessible public spaces, that saw a disabled man as still having so much more to do than just go home and die, that saw him as a part of his society instead of a burden to it, everything would have been so very different. Sure, he still would have been sick, and he still would have been dying, but hey. Perhaps he would have been encouraged to do a little bit of living first.

All any of us wants is to actually live.

My heart sank deep and black on election night. Yes, I absolutely cried with fear and desperation. But in the morning I woke up with the knowledge that this is not the end of me, or the end of The United States of America. It is just more work. It is hard work, and it feels remarkably brutal and hopeless. But so long as there is work to do, and so long as we are able to do even the slightest bit of it, we have to try.

And while it’s only a possibility that I have passed my condition on to my children, it is certain that I am passing on to them whatever world and country is left after all the work I have been able to do while I still am able to do it. So here I am, ready to put in the work because it is all that I can do.

image: Histopathology of a peripheral nerve sheath tumor (schwannoma) with H & E stain, via Wikimedia Commons.