We get out of the car and Ian carries Iliana across the parking lot, grateful she’s not actually asleep. The drive to Shoreline is just long enough to make her drowsy and she’s at the stage where a nap will ruin an already tenuous bedtime; afternoon errands like this are always a gamble.

The quest for poi and laulau makes the gamble a necessary one, and we bank on the novelty of the child sized shopping carts Central Market keeps by the front door. They work, thank goodness, and Iliana squirms out of her father’s arms to choose her cart. She sashays through the store, rattling off her own personal shopping list. Apparently we need all the gummy worms.

We follow her closely, directing her towards the freezer section. No, not that one, little love. The second one, where all of the other foods are kept. That’s where our food is.

We load up her cart with a king sized Portuguese sausage, laulau, three pounds of poi, and six packages of S&S Saimin. Oh, and this package of pink kamaboko. For the saimin, obviously.

I chuck some frozen mochi onto the pile; the kind filled with adzuki bean paste. Completely disinterested in this whole shopping routine, Iliana steers her cart towards the seafood section to check out the tanks of crabs she doesn’t understand will be somebody’s dinner. Ian follows her, leaving me to wander the aisles alone.

I feel selfish and terrible about the mochi, knowing I’ll be the one to eat almost all of them. Iliana doesn’t like adzuki beans and Ian prefers the ones filled with ice cream, while Jonas (who loves mochi as much as I do) will manage to pinch two or three before the whole pack is gone. I don’t mean to hog them, but biting into a red bean mochi is more than just food. That sweet, simple act takes me back to the days when I’d wander the aisles of Times Supermarket, pointing out everything I wanted that my mother couldn’t afford.

Always, at every single trip, I would beg her to add a pack of white and pink bean-filled mochi to our cart. Mostly the answer was no, because it was too expensive and we needed to buy milk and ground beef instead. Also, my sister didn’t like mochi and while Mom liked it enough to eat it, manjū was her actual favorite. If we were going to buy a treat, she said, it was going to be something that everybody could enjoy. Instead she’d send me off to grab big bag of Meadow Gold popsicles and I’d try (and fail) not to sulk.

But sometimes, on very special days, she would say okay and I would race back to the display case for a package of mochi before Mom could change her mind. We’d get the popsicles, too, because you have to have a freezer full of popsicles when it’s always eighty-something degrees out. But mochi has always been far superior to popsicles. I mean.

I knew enough to not even ask after kulolo, knowing that was something Grandma would bring home; a treat we’d share as if in secret. For sure Mom wasn’t going to buy something that literally only two people in the house ever ate. There just wasn’t room for things like that in her budget.

There’s no kulolo at Central Market, which I understand. It’s not exactly the most widely sought item of Hawaiian fare and I content myself with knowing that I could just get over myself already and get another bag of poi and some frozen banana leaves to make a batch myself. I could do this, but I haven’t. Not ever. So I can’t be too grumpy about the dearth of kulolo.

But I am grumpy about the frozen mochi, though I try (and fail) not to sulk about it. I know I could always go down to Uwajimaya for thawed mochi, if biting into one on the car ride home meant so dang much. But I choose Shoreline over the International District, better parking and easier traffic more important than unfrozen mochi.

But still, sulking. Just a little.

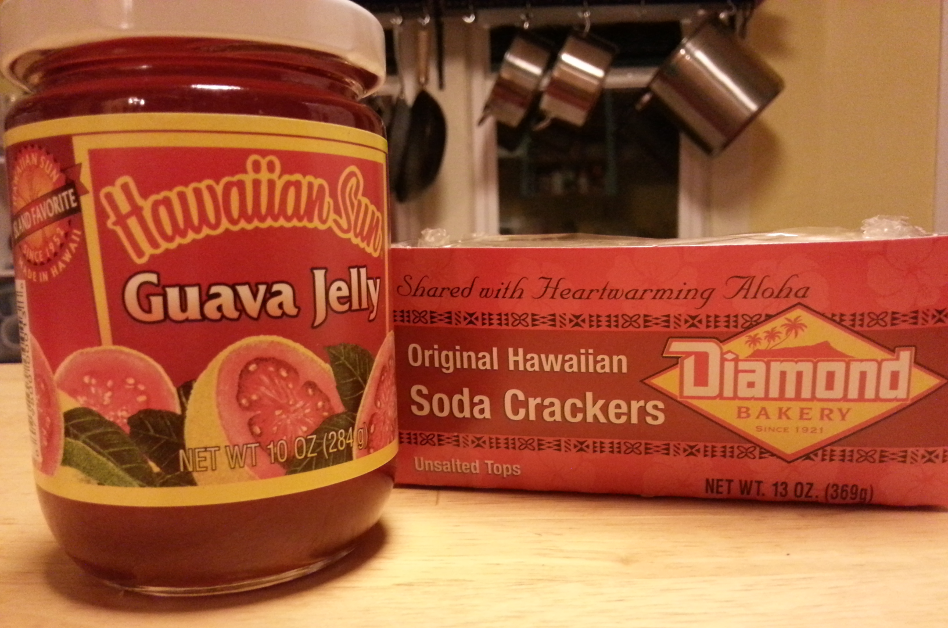

I turn down another aisle and stop in front of a display of crackers. I slip two packages of Diamond Head soda crackers into the crook of my elbow consider the Saloon Pilots and Royal Cremes. They’re expensive and I can’t quite commit to spending so much on basically flour and water. I leave the Pilots and Cremes on their shelves, then take a few steps toward the jellies.

They have guava jelly but not the jam, which triggers another flurry of memories. I prefer the jam, but we always got the jelly because my sister hated the jam. I’m not picky, so it always meant I ate whatever my sister’s texture issues could tolerate.

I understood it even then, knowing our family’s financial situation. Mom certainly wasn’t going to spend her shrinking food budget on two types of goop to put on crackers. It was simple mathematics: if Celine hated jam and loved jelly, but Celeste preferred jam and ate jelly just fine thank you very much, then put the darn jelly in the cart and be done with it already. It’s not personal or anything. Just logistics.

I laugh at myself now, the woman scrutinizing a tiny shelf of jellies in a tiny section of “Ethnic Foods” of a grocery store. I grab two jars of guava jelly and try not to harrumph too much. I’m just buying this shit because of nostalgia, after all.

No, not nostalgia. Homesickness. I am trying to feed myself something other that food, with all of this laulau and poi and agonizing over crackers that come from back home. I am trying to assert myself, culinarily speaking. I am trying to pretend for just a little while longer that living up here is still somehow okay.

I’m getting maudlin here in the cracker-and-jelly aisle, ready to cry and angry at myself because of it. If there’s no crying in baseball, then there really ought to be no crying in the crackers. I mean, really!

But I need more than crackers and mochi, more than even the laulau and poi can give me when we have them for dinner. I am struggling with buying all of my food in the ethnic foods aisle, or having to put up with parking and traffic if I want to shop at the 100% all-ethnic store. Most of all I am struggling with the implications of being ethnic instead of just being home.

I’ve been trying so hard, but twenty years later Seattle still isn’t home.

A stockperson walks towards me and I am jolted out of my self-absorbed reverie. He carries with him an easy familiarity with this section and even looks familiar to me. I know that sense of recognition is just due to his ethnicity. He’s some sort of Asian / Pacific Islander, like me. He looks like home. But, unlike me, his ethnicity isn’t ambiguous. I I probably look like just some white lady to him. That is proven when he looks over at me and smiles.

“Ah, somebody missing Hawaii,” he says. “You buy the jelly and remember your trip.”

I smile at him and nod, knowing it’d be unwise and probably unkind to dump all of my boo-hoo cultural struggling onto some dude who just wants to unpack his box of snack foods and go home. I walk away with my crackers and my sub-par jelly, finding Ian and Iliana in the seafood section. They’re still looking at the crabs.

“Ready?” Ian asks.

“That’s everything,” I answer, putting the rest of our groceries into Iliana’s little cart.

We go home and have crackers with jelly as a snack. I tell Ian about the guy at the grocery store. He nods sympathetically and holds my hand. He listens to me muse about shopping in ethnic foods; about knowing how lucky I am to shop in ethnic foods. About how being lucky doesn’t quite cut it most of the time.

“I’m not just missing Hawaiʻi,” I tell him, though he already knows. I take another bite of cracker, wishing for jam. Wishing for more than jam. I know I can get the jam next time; they were just out of it today. The jelly is fine. It always has been.

But somehow, today, it is just not enough.

This post originally appeared on Runningnekkid.com