My sister and I both have it, whatever it is. This condition may be rare in the general population, but it’s anything but rare in our family, at least on my father’s side. Neither of us can remember a time when we didn’t know about the tumors or that we could potentially get the tumors. Now if we could only get some solid answers as to what we’re dealing with and how to manage it long-term, that’d be great.

My sister has already had two rounds of genetic testing: once for NF2, which they diagnosed my father with in 1987, and another one to test for schwannomatosis when the NF2 results came back negative. By the time the NF2 test came back empty, we had done enough reading (and I had already had the MRI showing no tumors in my skull) so it was mostly expected. We had a gut feeling about schwannomatosis, the Neurofibromatosis variant that wasn’t even identified until after my dad died.

The characteristics of schwannomatosis seemed to correspond to the little information we were given by our parents. The disorder was always spoken of as some kind of mystical curse, but inside that cryptic language lived a few clues.

The curse sometimes skips generations, which is consistent with schwannomatosis. NF2 does not skip and if a child of a parent with NF2 does not develop the disorder, they will break the chain and their children will not inherit the condition. With schwannomatosis, however, my children could pass on this condition without ever developing it themselves.

The curse affects adults, and my father was thirty when he had the first of his many surgeries to remove spinal tumors. This surprised the doctors who diagnosed him with NF2, since that condition is considered a “children’s” disease, mostly showing up in adolescence. They wanted to study him because his case was so very rare, but my father refused to play “guinea pig” and he accepted his new clinical diagnosis of Neurofibromatosis type two.

This missed diagnosis is critical, since my sister and I have both been repeatedly told that our chronic pain could not possibly be due to our father’s condition because we had “passed the age” of onset for NF2. We’ve each been declared out of the woods, so to speak. As it turns out, they were telling us we were out of the woods for the wrong disorder.

And so we still don’t know what kind of nerve tumor condition my sister and I have. My sister’s schwannomatosis genetic test came back negative, and we were…shocked. When she first sent me the message, I couldn’t do anything but stare blankly at my phone for several minutes. We were so sure, you know? I told everybody about my schwannomatosis. I was expecting this test to reveal information I could just hand over to my geneticist. The confirmation of an already known fact, not the freefall of unanswered questions.

I haven’t had any genetic testing done yet. I see a geneticist at the end of February and theoretically that will be a more involved process than the lab work ordered by my sister’s neurologist. Or maybe it won’t – I am too scared to hold out much hope. But hope is there, as is the knowledge that genetic testing for schwannomatosis is still being developed. Literature about schwannomatosis admits “that current genetic testing doesn’t reveal a mutation in all affected individuals, and there may be additional genes responsible for the disorder in some people yet to be discovered.”

My sister’s neurologist himself said that all her most recent genetic test did was find that they did not find her to be missing one particular tumor suppressor gene shown to be associated with schwannomatosis. There are many such genes in the human body and schwannomatosis is still such a mystery that nobody is entirely sure how many of them are linked to it. And Neurofibromatosis itself – the blanket disorder under which NF2 and schwannomatosis both fall – may have even more variances than we know. Maybe our doctors are on the cusp of dicscovering a fourth kind of Neurofibromatosis. Maybe my sister and I will finally find fame in medical journals. (Hooray.)

This all seems like a gripping mystery of genetic code waiting to be cracked, but in the day-to-day life of chronic shooting nerve pain, I don’t really care about the nitty-gritty of genetics. I just want a treatment plan that recognizes me as having a tumor condition rather than a tumor. I can’t let my neurosurgeon or my insurance company treat my tumor as a one-off occurrence; I can’t let them deny me further imaging to investigate other potentially dangerous pain points in my nervous system.

I don’t really need to know what the name of my condition is. I don’t care what genes are affected or what codes my doctors need to enter when ordering more MRIs. But my insurance company cares. They’ll hold off as much as they can without the so-called right information, even though there might not be a way to get a genetic diagnosis. The family history should be enough, but this is bureaucracy we’re talking about here. This is paperwork. How many hoops will I have to jump through on legs that haven’t been able to jump in years.

I have a tumor pressing on my right sciatic nerve. I have nerve pain and numbness in other parts of my body not already investigated by MRIs. I am so distracted by pain every single day that I sometimes forget even the most basic things. I know have the same thing that killed my father. But without the smoking gun of a genetic marker, I don’t have a diagnosis. I don’t have a treatment plan or any kind of plan.

I was really hoping that my sister’s genetic test would give us a medical term for what is going on. Instead, we have to stick with the superstitious words of my parents. Call it a curse. Call it the tumors. Call it any kind of made up name because that is better than saying “my genetic nerve tumor condition”. Call it the thing that killed my father, and his father, and his father, and his. Call it the thing that is trying to kill me, and hope these words are enough to get me whatever medical care I need to keep it from doing just that.

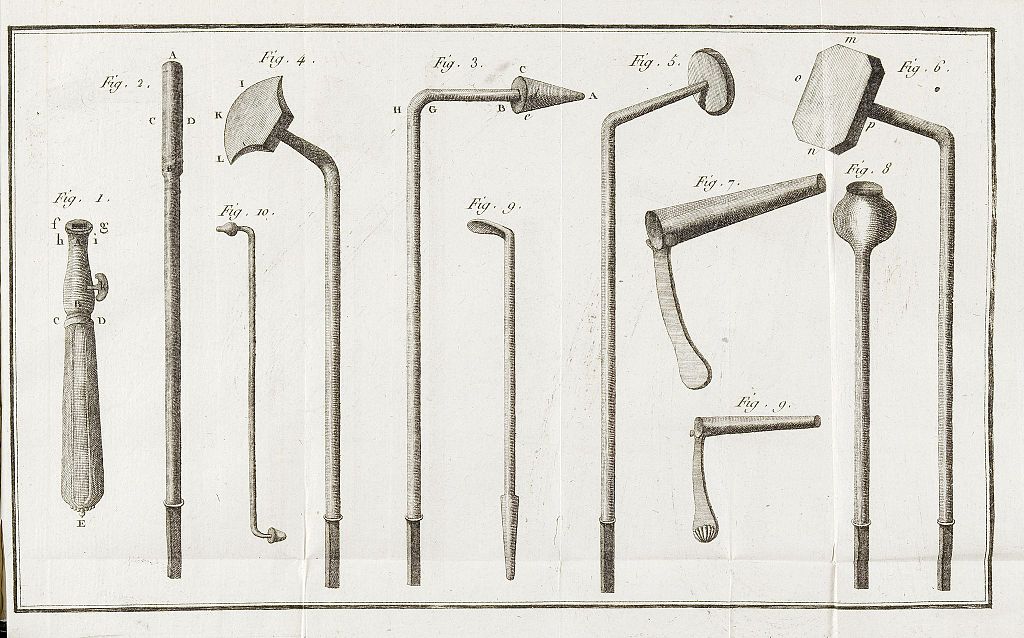

image: a selection of medical tools, via Wikimedia Commons