Last week, my five-year-old exclaimed that Donald Trump was the worst president of her entire life. She also had a few other choice words and I was a little caught off guard. We’ve been talking politics at home for sure, but her complaints about his finances didn’t come from our living room.

“Did you hear about that at school?” I asked.

She said they were talking about Trump at school, but not in class. Turns out she and her friends talk politics on the playground. And when someone is being mean, they admonish their peers to stop being a Donald Trump.

I admit I sighed with relief. I know Seattle likes to think itself a progressive town, but I’m never quite sure how it’s going to play out. And it’s even more difficult to tell when it comes to the children.

All weekend after the inauguration, my daughter recited the poem her class learned for Martin Luther King Jr. Day. It stung deeply, hearing Dr. King’s messages watered down and handed out to our youngest citizens without the urgency and bite that make his work more and more relevant as the years go by. It’s reckless, to let yet another generation absorb the ideals of non-violent protest without understanding the government’s purposeful obstruction of civil rights and how much work there is yet to do. How little of Dr. King’s dream has actually come to pass and how responsible we are for seeing it come to fruition.

I am descended from Indigenous peoples of this colonial superpower. While I’m glad to an American, my citizenship comes with the knowledge that the country I love absorbed my parents’ Pacific Islands after the Spanish-American war. I have always known this country’s actual origin story. It is the story of how my family’s nationality changed hands while we remained exactly where we had always been. That’s just a fact. And like any other parent, I help my children see through our family lens. My children are accustomed to hearing me challenge the things they learn in school about the first Thanksgiving, or the Fourth of July. It’s just part of who we are. That wasn’t anything new or interesting when I was growing up in Hawaiʻi, but here in Seattle, it can feel like an anomaly.

So when my daughter brought up segregated drinking fountains – “they used to do that, Mommy” – I had to say something. It seems unlikely that she’ll learn her nation’s difficult truths under this administration and I can’t let sanitized history keep taking root. It’s a parent’s duty to inform our children as much and as well as we can, so that they can learn the ideals of equality and justice at as young an age as possible. So they are loyal to the concept of our United States, rather than any politician or public figure.

“The government saw Dr. King as an enemy,” I said. She looked at me as quizzically as you would expect, those matter-of-fact words contradicting the lessons she’d learned in class. “They wanted to keep people segregated, and Dr. King was making it hard to keep it that way.”

“That’s not fair,” she said, because children see what some adults refuse to.

“No, it isn’t,” I replied. Because it’s not.

It might sound quaint to have a five-year-old exclaim that she is living under the worst president of her entire life. But those words give me hope in a way I hadn’t anticipated, because she didn’t only get those ideas from me. She’s bringing those ideas home, from her friends. From the future voters who will be in charge of whatever country we leave them with in thirteen years. They’re talking about this stuff on the playground. They’re five, and they’re already grasping at the ideals they’ll need to rise up against injustice. And so help me, I’m going to do whatever I can to leave them a country worthy of their sharpness and their potential.

It is the very least I can do.

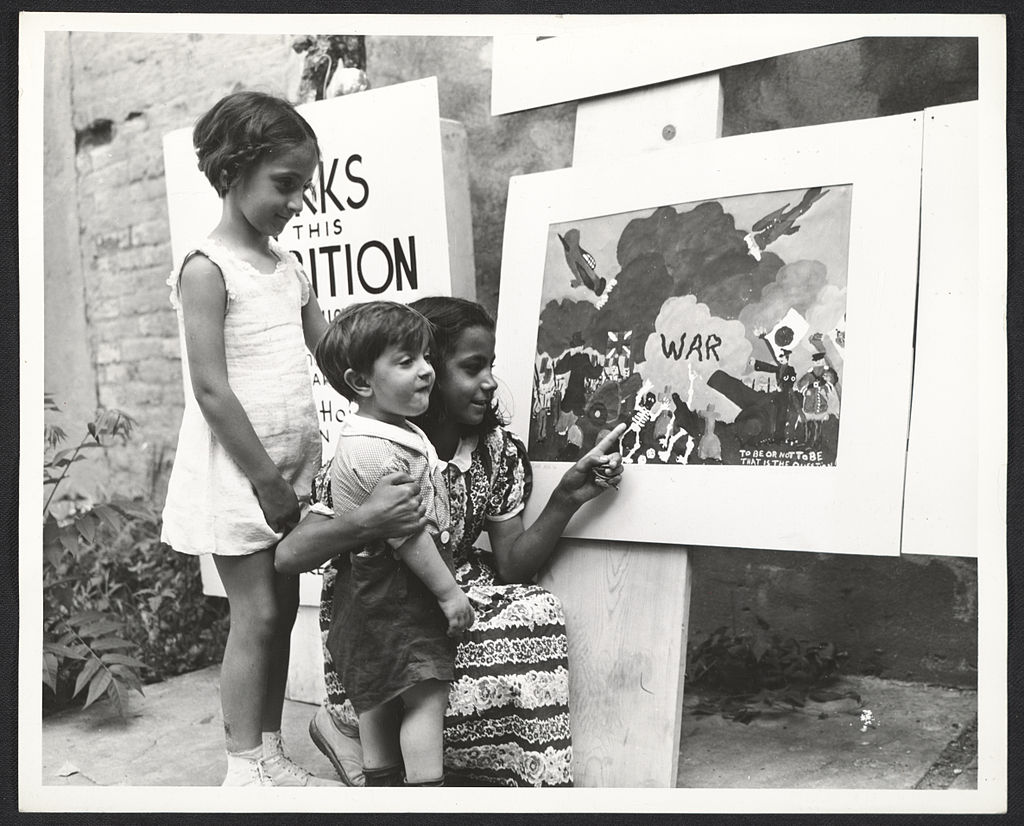

image oftwo girls and a little boy viewing piece of art depicting war, via Wikimedia Commons