It was hard not to let myself get carried away with pride when my Physical Therapist gushed over the progress I’ve been making. She noticed that my legs weren’t shaking in protest during one of her awful resistance band routines and congratulated me on a job well done.

“You’re so much stronger than you were when I first met you,” she said and before I realized it I grinned like a child with a strawberry scratch-and-sniff sticker at the top of their spelling test.

It’s true, though. I am stronger. I’ve been in PT for almost six months now and I can tell how much of an impact it has on my everyday life. I also know more about my limitations; how far I can bend down or raise my leg before the tumor pinches my sciatic nerve and I begin to stumble from pain. When I’m more careful with myself, I don’t aggravate the nerve as much and so I feel better. It’s a nice feedback loop.

I also do my exercises every day. An hour of them, although sometimes I’ll do half that if don’t have the time. I usually pay for it the next day, and if I try to skimp two days in a row I better just go ahead and call that third day a total loss. I can feel the benefit of doing my exercises; of complying with my health care provider’s assignments. My PT says that she can tell I’m working really hard and I can’t help but thrill at the recognition.

“I’ve been a good girl,” I laughed like a puppy waiting for a treat.

But this isn’t a matter of me being good. Mostly it’s a matter of circumstances coming together in the right enough way to allow me to focus on managing my nerve tumor condition. Me doing an hour a day of exercises that leave me exhausted and fog-headed is not just a matter of goodness. It’s a commitment, yes. But also, it’s just plain opportunity.

“It’s because I don’t work in an office,” I said when my Physical Therapist remarked again that I might be one of her only patients doing their “homework” every day. I know this isn’t the whole of it, but also I know just how what a difference it makes.

My father worked full-time for the City and County right up ’til the surgery that turned him into a quadriplegic. He drove from Kāneʻohe to Kaimukī to Waikīkī and then to his office in Honolulu every day and then back again every evening, sitting in the stifling Oʻahu traffic that made us all irritable and tired. When we got home, it was the ridiculousness of dinner and bedtime routines with children, then a moment spent in the company of his wife before hitting the sack to get up for the whole mess again the next day. Where he would have fit an hour of PT exercises a day and weekly in-clinic sessions, I haven’t the faintest idea.

Sure, he did a lot to try to “beat” his disease, a condition that to this day has no hope for a cure. He took a lot of walks because walking was more comfortable than anything else, and took long afternoon naps on the weekends. He tried all sorts of special diets even though his culinary preferences tended towards saimin stand rather than produce section. As a child I felt like our entire family’s world was wrapped up in my father’s Neurofibromatosis, but now that I’m the one engaged in battle, I understand how little care he actually had before his paralysis.

I haven’t worked in an office for almost eight years. I’ve been a stay-at-home parent and would-be writer with the financial as well as emotional support of a husband whose high-skilled, high paying job has flexible hours and excellent benefits. It might be an enormous pain in the ass (and I do mean that literally, since my tumor is right below my gluteus maximus) to build my life around my condition, but I never forget that I am able to build my life around it without giving up my financial security.

I wouldn’t be able to be a “good” patient if it wasn’t for the lifestyle afforded by my husband’s salary, or the medical coverage that lets me do weekly PT sessions for a measly five dollar co-pay. And I wouldn’t be able to practically function in my own home if it wasn’t for the physical support he has provided. He’s made huge sacrifices to incorporate my condition into his life. My mobility has been declining pretty rapidly and I can no longer do most of the household chores that I used to do while he was at work. It’s taken a lot to figure out the logistics of keeping our household running, and my husband has been the one to shoulder almost all of the burden. The kids have been helpful too, of course, but still. He picks up slack caused by my disability, and without him I would be much worse off and in so much more pain than I already am.

I know that it’s up to me to get off my ass and do the hour of horrible exercises that leave me feeling like a wrung-out dish rag, and I do them. Every day, whether I want to or not. And I never, ever want to, let’s be perfectly clear. I hate my exercises. I hate all of the accommodations that I have had to incorporate into my life because of this painful genetic condition. But I do my exercises. I make the accommodations. I get stronger, and find ways to be as capable as possible with whatever mobility I still do have. And I understand that this is not me being good, this is me being blessed. Being able to spend my time focusing on my chronic illness might seem like a crappy privilege, but it is a privilege nonetheless. And I hope I never, ever forget it.

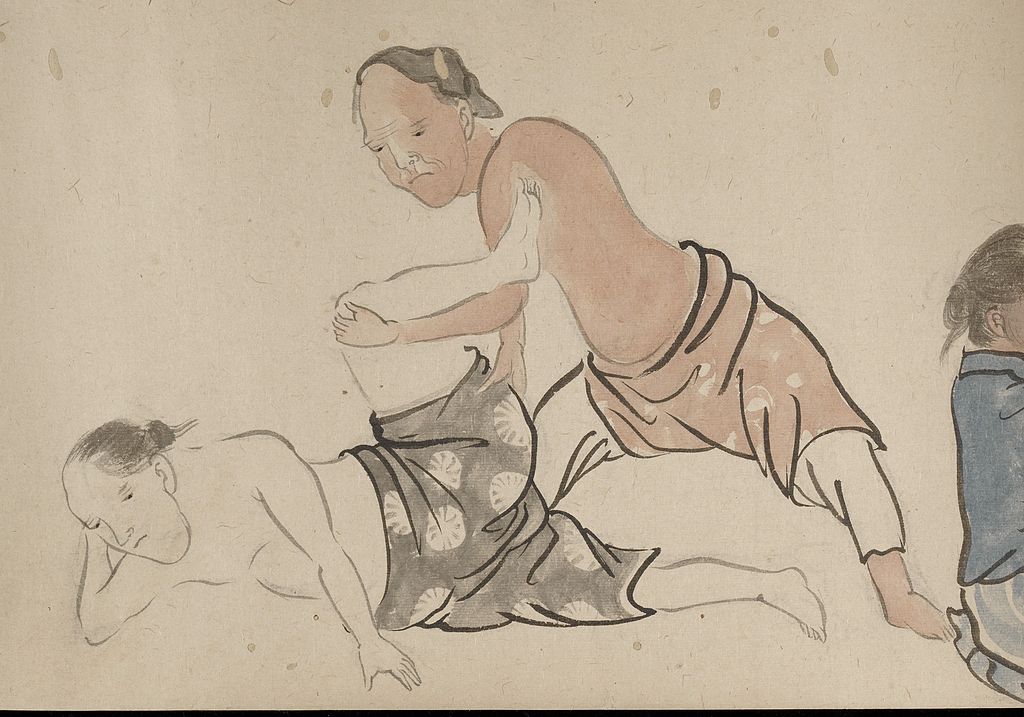

image of a Japanese Scroll showing techniques for Physiotherapy, via Wikimedia Commons

I love this, that you acknowledge the privilege of being able to take care of yourself. And the blessing that your husband is able to and does make it so. That’s a beautiful thing, that makes your recovery a partnership. So, so many cannot do what they “should”, and they are so often castigated by their care providers because of that: not praised for what they do; not provided with the means to make their lives just a little easier so they can do better. It’s like, you have the “luxury” and so you do those damn exercises in honor of those who can’t.

It is a blessing to have the means some of us have to be able to take care of ourselves, and I really appreciate your recognition of the many who don’t have the same opportunities.

This is also so beautifully written! Thank you.

Thank you so much, Holly! My husband really has been a partner in the management of my condition, which is another layer of privilege – this time, his. He is able bodied so far and can do his job well. We’re making the absolute best out of a less-than-ideal situation and it’s a lot of work, but we do have a lot of tools at our disposal. I wish it wasn’t so – I wish that everyone could have the same ability to center their own care. It seems so fundamentally human, but somehow in this world right now not everyone can do this. It is a real shame on the societies that make it difficult for people to take care of themselves.