Books, like people, can come into your life at exactly the right time. Evocative prose and a gripping story can meld themselves perfectly to ideas that have been percolating in the back of your mind for years. Difficult truths that would have been interesting at any other time in your life sink in deeper, thanks to the mystical sleight of hand present in any capable narrative.

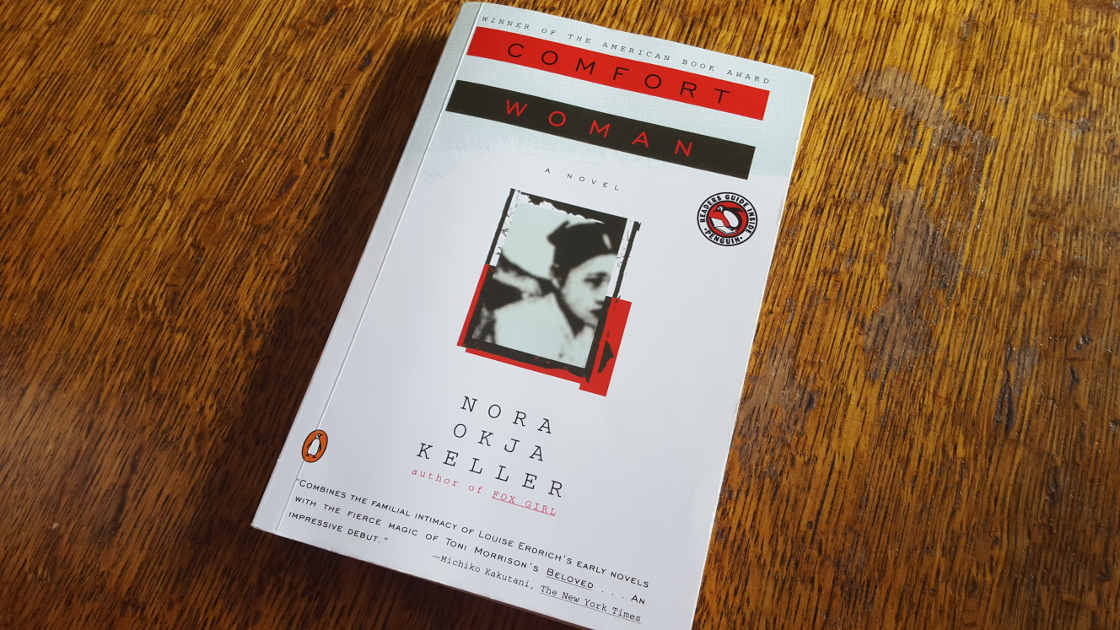

This is how I met Nora Oka Keller’s stunning, brutal 1997 debut, Comfort Woman. If I had read it six months ago, or six months from now, perhaps I wouldn’t have been quite as affected by this sharp, harrowing read. Three years ago I wouldn’t have had the fortitude to finish it at all. But I read it this Spring, over the course of two or three weeks that had me also making arrangements to place my mother’s ashes in a beautiful koa-framed niche at Diamond Head Memorial Park.

My mother’s been gone for nearly five years, which is a long time to hang on to someone’s ashes if you don’t mean to hang on to them forever. But Mom never gave us any directions for what to do with her remains and it’s taken us this long to figure out the just right thing to do. We’re intimately aware that this is the last thing we can do for the woman we knew best and least at the exact same time.

I’ve spent most of my life angry at my mother. Being her daughter was extraordinarily difficult and I blamed her completely for “how she was.” It was only after her death that I started digging at the enigma that she was, learning more than I cared to learn about WWII in the Pacific. While grieving the volatile woman whose tenderness I so earnestly craved, I opened my eyes to generational trauma and the painful resiliency of Pacific Islander children raised in the aftermath of concentration camps and so-called liberation.

I knew, for example, that my grandmother refused to tell my mother who her biological father was, but I never realized that Grandma Olga got “mysteriously” pregnant right after the 1944 Battle of Guam. After the brutal occupation of Guam where my grandmother’s brother, Jesus, was killed by a Japanese land mine. And while I knew that Mom was sent to Hawaiʻi for boarding school in 1953, I didn’t understand how much of an escape that was intended to be. Shielded from the brutal undercurrents of our family story, all I saw was my distant, brooding mother, never contemplating the trauma or loneliness that helped shaped her into the woman I often feared and sometimes despised.

It is just this kind of traumatic, war-torn family history that drives the narrative of Comfort Woman. Grisly secrets play out in the life of a young girl trying to get through the turbulent years of adolescence with no clue about her mother’s traumatic past. No idea that her mother Akiko received her name at the camp she was sold to by her own sister. No idea that her mother was forced into sex slavery, or that she managed to escape but never really left the camp behind. She cannot know how much her mother loves her because her mother slips into long, terrifying psychic trances that could be construed as insanity. Beccah herself views her mother’s “gift” as a shameful mental illness and deeply resents Akiko’s inability to care for her when she slips away.

I feel a solidarity towards Beccah; am familiar with her plight. My mother’s periods of withdrawal may not have been nearly as dramatic as Akiko’s, but they were definitely terrifying. When Beccah wraps her leftover school lunch in a napkin in hopes that her mother will eat it later that afternoon, I am filled with the familiar anxiety of wondering what it was my mother needed to make her start seeing me again. I would have done anything, but nothing I tried brought my mother back before she was ready. In Beccah’s waiting for her mother’s return, I see my own.

It also helps that Beccah’s story takes place in the multicultural chaos of my own Hawaiian island. She hides beneath the Ala Wai bridge when she is terrified and angry and I can feel the location so vividly I almost wrinkle my nose against the smell. I thrill at reading Pidgin in the dialogue and the descriptions of scenery, characters, culture. The richness of Beccah’s observations are in contrast to her standoffishness as a narrator and I understand why Beccah is so reserved in her relationships, her telling of the story to us the readers. I wish I could get more from Beccah; have her tell different parts of the story because I am sure there is more to tell than just the anxious heartache she relays.

She tells of a childhood in the shadow of he Korean mother and her strange, superstitious ways. She shares the desperation of a biracial girl living in Hawaiʻi trying so hard to fit in, or to at least not embarrassingly stand out. These struggles are familiar to my own and Beccah’s failures ring true and deep, for all their superficiality considering the depth struggle present in the rest of the story. But girlhood Becca does not know of these struggles. All she knows is the worry over her mother, over her unpopularity at school, her isolation. She endures repetitive abandonment of a mother physically present yet absolutely unavailable, and her anxiety is so real that I find myself having to put the book down for while to remember that this is merely fiction.

Immersed in the narrative, I also feel a deep empathy for Akiko, the woman who knows too well how death and displacement wreak havoc on the intimate bond between mother and child. Her passages span the entirety of this heartbreak, from grieving the death of her own beloved mother, to the desperate protectiveness she feels when looking into her newborn daughter’s eyes.

Akiko spends days, years, gazing at the perfection of her daughter. So many paragraphs are dedicated to watching Beccah, thinking about Beccah, marveling at the completely ordinary miracle of Beccah’s healthy development. Akiko loves her daughter with utter devotion, and the tragedy of the story is that Beccah never really knows.

The tragedies of Akiko’s own life are horrifying, and she relays some of the most grisly details with a kind of stunned detachment. Orphaned as a young girl and still called by her birth name Soon Hyo, she is sold to the Japanese as a dowry for her older sister’s wedding. When the soldiers ask the sister if she would like to come as well, Soo Hyo hopes “she at least had a momentary fear that they would take her too.” In this simple sentence Soon Hyo acknowledges the speculation, the fear of the unknown future lurking just ahead. Later, when a seventeen year-old “Comfort Woman” is brutally slain for speaking out against both the camp and the Japanese occupation, the disturbing treatment of her body is mentioned as if in passing. This offhanded remark about the inhuman cruelty at the hands of the soldiers makes the scene even uglier.

Soon Hyo is remade into Akiko, taking up the name of the woman whose murder leaves a space that needs to be filled in the sex encampment stalls. She eventually escapes, only to be taken to a Christian mission where she is singled out by the head missionary for her youthful appearance and mature nature. Akiko sees right through him, and what she sees is a way forward.

Akiko’s searing observations are the root of her psychic gift. She “sees” throughout the entire book, whether it is into the heart of a foul-breathed woman or the eerie shadow Induk, who she views as the murdered Akiko who came before her. She sees her daughter Becca again and again, even as she retreats into her spiritual world of ghosts and visions. It is in this world of dual focus that she begins the recording of a cassette tape that will bring mother and daughter together at last.

In listening to her mother’s tape, and going through her mother’s secret hideaway treasure box, Beccah finally begins to see her mother in return. She discovers the awful truths about her mother’s identities and in the end calls her mother by her girlhood name: Soon Hyo. She honors her mother in death the way she had never been able to while enduring the erratic, terrifying specter of her mother in life. This is the tearful, healing crux of the story. This is as close to where I am right now as I think a story written by a stranger could ever get.

Today my sister and I are trading emails, trying to decide at last on a koa urn to hold our mother’s ashes for placement at Diamond Head. When my mother died, I was too angry with her to choose her urn right away. She’s been in a blue plastic box, standard issues from the crematorium, for the past five years. In the space between her death and today I have come to learn about her and the world that helped create her. Helped create the difficult tapestry of us. I may not have the gift of a cassette tape or newspaper clippings specifically chosen by my mother to aid in telling me her story, but I do have truths uncovered through my own determined seeking. I might be jealous of Becca and the treasures her fictional mother was able to bestow, but I am doing my best to find my mother regardless.

Comfort Woman ends with the painful truths of Soon Hyo’s life and Akiko’s death hanging in the air, exposed but unresolved because there can be no resolution. All there can be is Beccah grieving her mother and slowly, tentatively, going on with her life. Like Beccah, I not only have to mourn the passing of my mother, but the passing of what I wish our relationship had been. And like Beccah, my work now is to just accept the enigmatic, troubled woman who raised me. To honor her because she did love me, dearly. She sacrificed so much, endured so much so that my siblings and I could have a life free from the troubles she knew as a girl. I owe her my life, literally of course. But also I owe her so much more. I feel happy, liberated, that I finally am able to understand this truth. And though it was difficult to sit with the entirety of this brutal narrative, I am thankful that there are books such as this to help me reach one more kernel of empathy that my mother so richly deserves.

I thought you had taken a trip back home some time ago to return your mother’s ashes there. I’m glad this book has given you the closure needed to take that step.

We were back home to choose the niche. Even that step was overwhelming, and now we are ready for the next.

Mahalo for being here, W.